Mountain: The Eiger

Summit Date: March 19, 2020

Route: The 1938 Heckmair Route (first ascent route)

“Anyone who returns from the Eigerwand cannot but realize that he has done something more than a virtuoso climb: he has lived through a human experience to which he had committed not only all his skill, intelligence and strength, but his very existence.”

-Lionel Terray, Conquistadors of the Useless

“Yes, we had made an excursion into another world and we had come back, but we had brought the joy of life and of humanity back with us. In the rush and whirl of everyday things, we so often live alongside one another without making any mutual contact. We had learned on the North Fae of the Eiger that men are good, and the earth on which we were born is good.”

-Heinrich Harrer, The White Spider

Luckily (or not), our ascent of the 5,000ft Eiger North Face (or ‘Eigerwand’ or ‘Eiger Nordwand’) in mid-March 2020 may have been on the quietest days in the face’s history of climbing since its first attempt in 1934. No summertime cow bells ringing in the rugged hillsides of Alpiglen above the town of Grindelwald, no cars and honks were noticed, no sounds of ski lift machinery, no joyous skiers on the hillsides of the Jungfrau ski resort which sits at the foot of the Eiger, few trains were in operation (and solely for construction workers). Not even any sounds came from the sky as we climbed in perfect, bluebird weather for three days.

Frankly, I could’ve used more cow bell. Among the reasons I climb, isolation is not one of them. I appreciate the sights and sounds of civilization from a climb which provides significant psychological aid. We did, however, see several helicopters fly by delivering goods and construction materials to the future site of a new lift within the resort, along with several Swiss Air Force F-18’s practicing formations through the beautiful Berner Oberland valley.

Jon Krakauer wrote in Eiger Dreams: “I didn’t want to climb the Eiger, I wanted to have climbed the Eiger.” This is a sentiment I think most climbers can understand at some level. For years this quote has haunted me. There are many climbs to which I could solidly attribute this feeling. I knew, however, that whenever I would finally step out onto the snowy slopes of the Eiger, I didn’t want to have this feeling. The Eiger is just too dangerous; too big; too bold. I always knew that if I felt this way, I would simply turn around. I wanted to be in it, and enjoy my time wrestling with the alligator. Luckily, both Priti and I were itching to attack, having fun the whole way.

We arrived in Grindelwald, Switzerland from Chamonix the day before our intended climb and took an overpriced 1hr train ride to Kleine Scheidegg, the central hub of the Jungfrau Ski Resort. Kleine Scheidegg is crowned by the historic and elaborate alpine resort, established in 1840: Hotel Bellevue des Alpes (where ‘The Eiger Sanction’ and ‘Nordwand’ were filmed). Many of the more well-sponsored Eiger climbers throughout history have stayed here. But not all. You would have thought that the Third Reich could have at least put up Karl Mehringer and Max Sedlmeyer up for a few nights!

Many climbers discreetly bivy near the foot of the Eiger within the ski resort, or on the floor of the restaurant at the Eigergletscher complex (the uppermost hub of the Jungfrau ski resort). However, we were expressly denied permission to sleep on the restaurant floor. Furthermore, we also found the Women’s and Handicapped restrooms permanently locked. All of the construction workers are male, and the proprietor must have caught on to the unexpected guests of the Women’s restroom from recent Eiger Conquistadors.

If a climber wants to step up their bivouac accommodations slightly above a bathroom stall or a restaurant floor, they can stay at the Eigergletscher Guesthouse (hostel). However, with the ongoing construction of a brand-new, state-of-the-art gondola which will link Grindelwald directly to Eigergletscher by the end of 2020, the guesthouse is exclusively housing construction workers until the end of the project. There is another hostel at Kleine Scheidegg (Hotel Bahnhof), but it had already been closed for a few weeks due to Coronavirus precautions. Staying at Eigergletscher or Kleine Scheidegg is ideal so that you can start your first day of climbing as early as you like (however, many climbers do start their first day from the 7:00AM train in Grindelwald). During summer months, climbers might also base camp in pastures beneath the face, as Mehringer and Sedlmeyer did for their attempt in 1936, however the train is so expensive that base camping in Grindelwald is now the norm while waiting for weather and conditions.

The thing about the Eiger is that even if the forecast looks splitter, you never know when the semi-mythical and unexpected ‘foehn’ will show up. These are southerly winds that blow on the north side of the Alps in winter. The foehn (literally meaning ‘hair dryer’) frequently surprises climbers bringing sudden bursts of warm air and stormy weather.

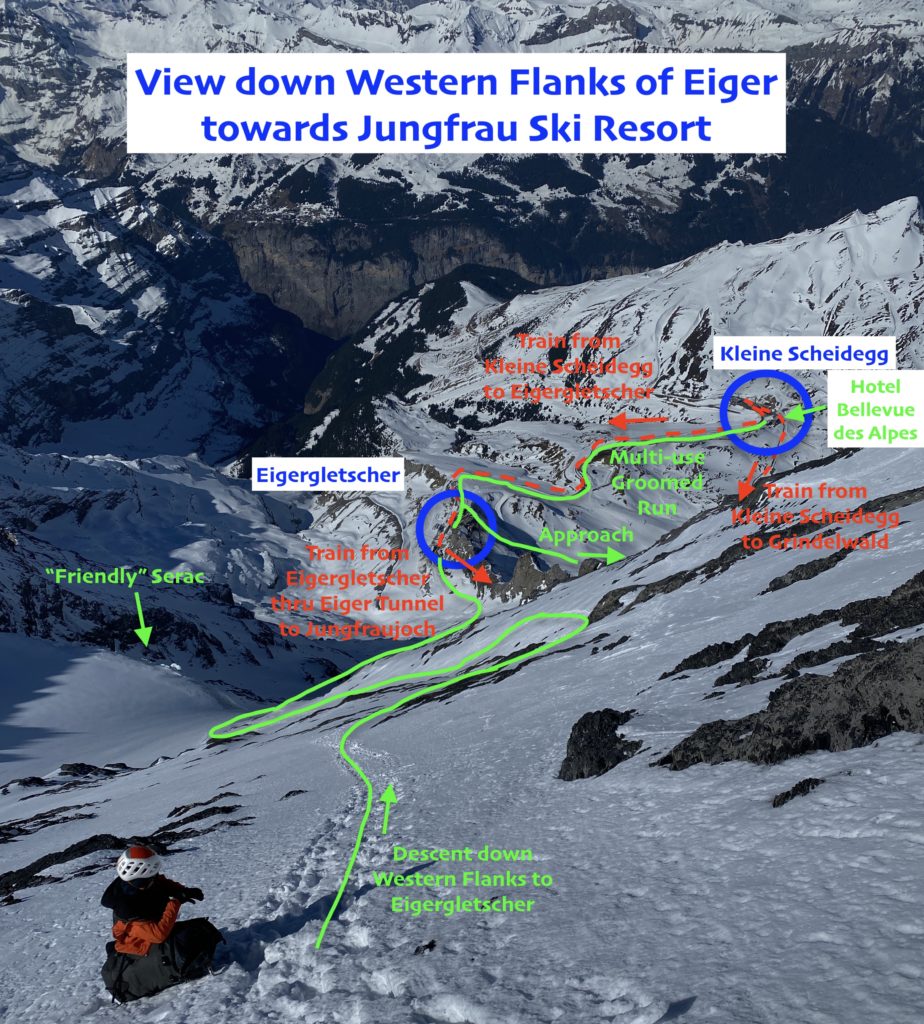

The Jungfrau ski resort is unusual in that its primary artery is a 128 year old railway: the “Jungfraubahn”, highest railway in Europe. A climb of the Eiger usually begins with an expensive 1hr train ride from Grindelwald to Kleine Scheidegg, then a change of trains for another 10min ride up to Eigergletscher. Exiting the Eigergletscher deposits one out onto the lower slopes of the North Face. The train, however, does continue on, burrowing up through the depths of the Eiger and on to a high saddle (the “Jungfraujoch”) between two of the Alps’ most impressive 4000m peaks: Jungfrau and Mönch. From Kleine Scheidegg, one gets an incredible vantage point for the skyline of these three behemoths: Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau. Modern folklore has it that the Monk (Mönch) guards the Virgin (Jungfrau) from the Ogre (Eiger). The actual German word for Ogre is “Oger”, and the true etymology of the word ‘Eiger’ stems from a curious and long-forgotten amalgam of middle high German, Swiss vernacular, and Latin for something like “high peak”.

There is a multi-use, groomed run which connects Kleine Scheidegg up to Eigergletscher. Trying to save some money, we skinned up this run instead of buying a train ticket to reach Eigergletscher (only 30-45min of easy skinning). Then, we skied down an amazing groomed run for 6 miles and 4500ft of descent from Eigergletscher all the way down to our hostel next to the train station in Grindelwald. All day, the ski resort was bustling and vibrant, and no one at the resort or the train station expected any disruption of service any time soon due to Coronavirus precautions. With the Eigergletscher Guesthouse closed due to construction, Hotel Bahnhof closed due to health precautions, and the Hotel Bellevue des Alpes open but too ritzy, we planned to discreetly bivouac near Eigergletscher. Upon arrival back at Grindelwald, however, we got word that the entire resort (lifts) and the trains would discontinue operation that evening for the indefinite future due to Switzerland’s precautions against Coronavirus. A final and devastating setback.

We had originally come to Grindelwald due to a large high pressure system which was bringing a week of unusually phenomenal weather to the otherwise grim mountain. We’d planned to at least visit in order to understand the approach, logistics and start to observe the conditions on the mountain.

The lack of train meant an extra 6 miles and 4500ft gain of approach to the mountain…a mere “sit-start”. We were not yet about to give up and call it quits. Back home, Chamonix-Mont-Blanc lifts were still running under normal operations and both France and Switzerland were not under lockdown, so there was no urgency to leave at the time.

As luck would find it, we found a companion for our laborious day of skinning our heavy load up to Kleine Scheidegg. Another BOEALPS veteran happened to be in Grindelwald at the same time: Fabien Mandrillon. He is revered within the club for his years instructing classes and for being Head Instructor of the Basic Rock Class (as we had also been). He had emigrated to Zurich before we joined the club, and we had hoped to meet him at some point on our Sabbatical. Having pleasant company under these unfortunate circumstances was certainly a delightful way to start our adventure. Surprisingly, we saw only a few other backcountry skiers on the hike up from Grindelwald. The resort had even groomed the track from Grindelwald that morning expecting the closures would not to keep people off the slopes. It was a beautiful day after a light dusting of fresh snow the day prior. If this situation were in Washington, the trail would have been packed with backcountry skiers!

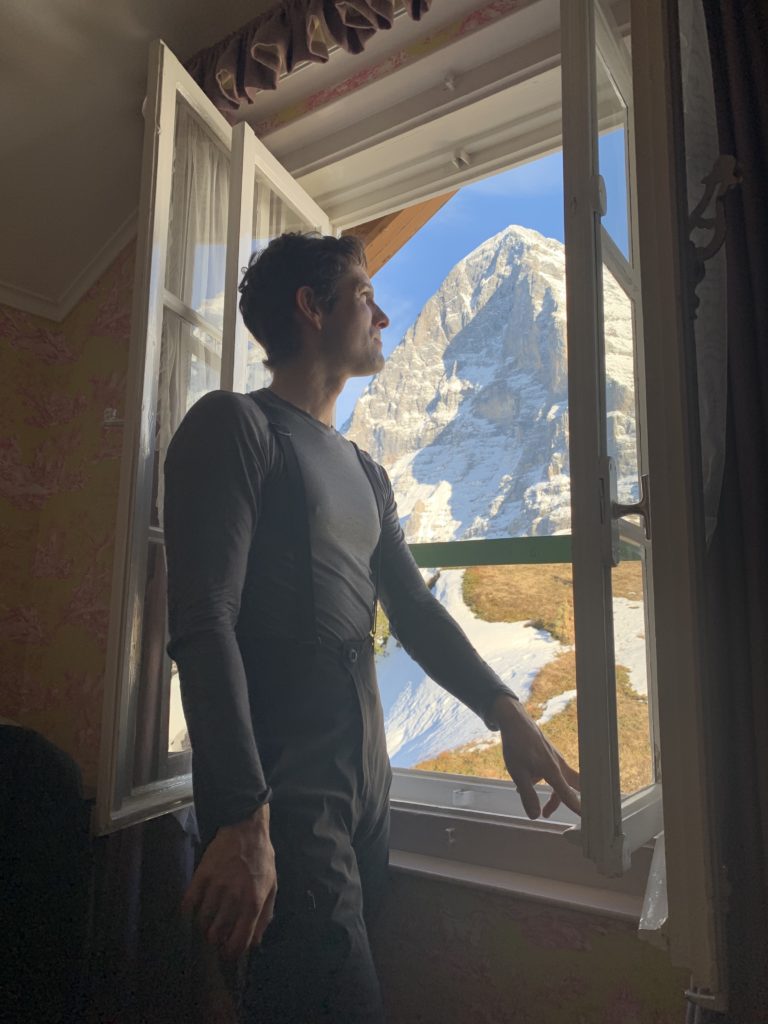

Once we were back up at Kleine Scheidegg, under full expectation of sneak-bivouacking within the resort, we were delighted to find one set of accommodations still open (under extenuating circumstances). The grand Hotel Bellevue des Alpes had remained open a few extra days because of a few VIP guests which they were unwilling to expel. Thus, we took a sizable chunk from our Sabbatical budget to fork over to one night of luxury before we took on the Eigerwand. The evening was reminiscent of one of my favorite films, Wes Anderson’s ‘Grand Budapest Hotel’. The entire establishment glistened with immaculate, Old World luxury. Only the remaining handful of guests were being served the magnificent 4-course meal (indeed, one of the greatest in my life) within the halls of the elaborate dining rooms. At dinner, the guests were seated segregated by an optimal number of empty tables so as to assuage our newfound distaste for social interactions. Under strict orders of “No sports attire during dinner”, we sheepishly dined wearing our Eigerwand armor and our complimentary, fuzzy bathroom slippers while the other guests wore formal wear of suits, ties, dresses, and formal shoes. As we found out later, the few guests remaining were elderly patrons going back decades, one of whom had lost her husband of 47 years the week prior, escaping to a memory of their life together.

Feeling the rush to appreciate our accommodations with the clear acknowledgement of our pre-dawn start, we spent a few minutes alone in each of the exquisite rooms of the establishment, excitedly recollecting the various scenes filmed there for The Eiger Sanction: the billiards room, the parlor, the bar, the lobby, even the concierge desk. The tolerant bartender with an immaculately groomed beard and pencil-long mustache, served us some truly delightful concoctions ginger ale, tonic water, and citrus: no summit, no party.

We wryly noted that whenever we expressed our intent on climbing the Eigerwand, nobody would bat an eye. Naturally expecting some expression of praise (“vanity is one of the prime movers of the world”), we were taken aback at the utter apathy to which the world judged our sepulchral pursuit. We were not special! “Eiger-birds” (hopeful climbers) were a dime a dozen, and we were to receive no accolades before or after our adventure.

From our bedroom that evening, we watched winter’s shy sun set early on the North Face of the Eiger, and the nocturnal eyeball of the “Stollenloch” wake up to illuminate the lower slopes.

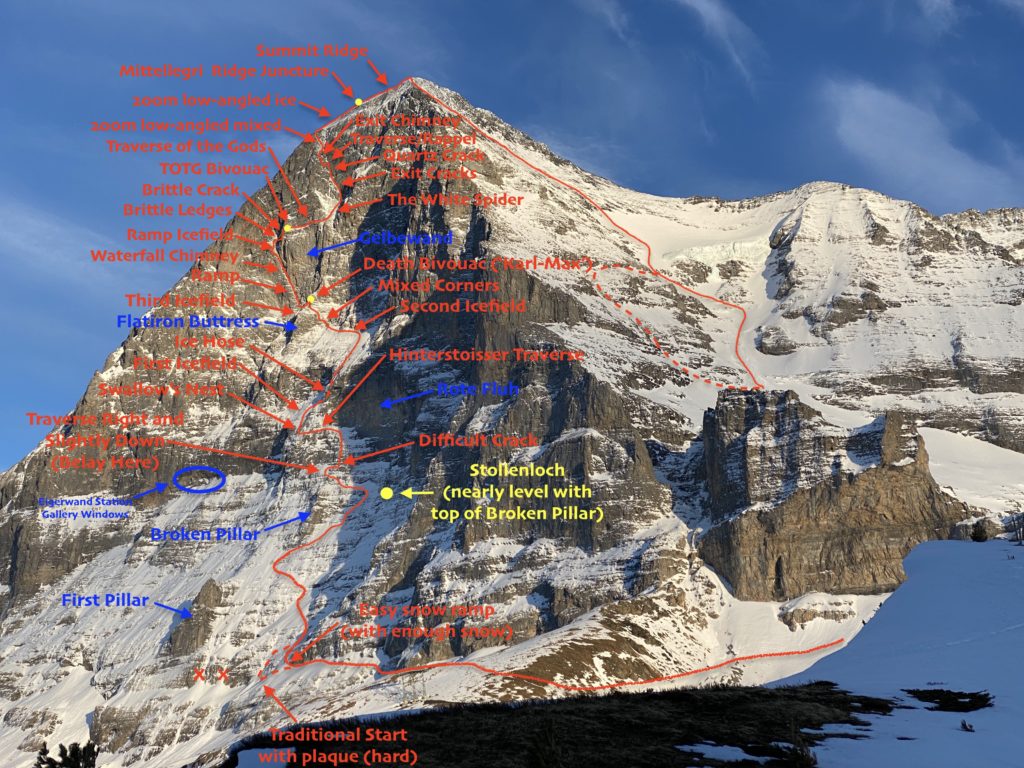

At the turn of the 20th Century, enterprising Swiss railway Engineers blasted an impressive tunnel through the heart of the Eiger, from which two windows were poked through Eiger’s North Face about a third of the way up. One upstream (the “Eigerwand Station”) on the looker’s left side of the face, and one downstream (the “Stollenloch”) on the right side. The Stollenloch (“Door 38”) is a small, purely utilitarian window which was used to jettison debris from the early railroad construction over a century ago and was never a tourist observation window. Some climbers have approached by walking up the railroad tracks and exiting the Stollenloch to bypass the lower snow slopes of the face. Approaching via the Stollenloch is generally considered taboo, while nearly all climbers take the train up to Eigergletscher (and down as well). We have to start somewhere, and it’s not Bern! Still, it’s worth noting that Kurz and Hinterstoisser biked from Berchtesgaden, Germany, nearly 400miles away…perhaps the true sit-start for the Eigerwand! When there is enough snow, climbers stash skis up high for a victory ski lap back down to Grindelwald to top off the climb.

The Heckmair route goes very near the Stollenloch which has given this window quite a reputation through the climbing history of the face. The other gallery (the Eigerwand Station) is not near any other popular climbing route and is on the far left side of the face. The Eigerwand Station is an engineering feat, clearly visible from the valley floor, consisting of a series of several large balconies (later converted to glass windows) that mar this limestone sculpture. Since the Jungfraujoch extension opened in 1912, tourists have been able to lean over the vertiginous parapets to marvel at the face’s dizzying slopes. The balconies were even outfitted with paper bags in the event that a tourist experienced any physiological discomforts!

The Eigerwand Station was a 5 minute train stop solely for tourist observation from 1912 until 2016, when newer, faster railway vehicles were incorporated, and this renowned observation point was put out of service. Interestingly, since the Eigerwand Station’s closure, “much of the publicity material fails to acknowledge that this viewpoint station ever existed” (Wikipedia). Quizzically, the iconic and celebrated Eigerwand station was axed in order to add one more train and reduce travel time to Jungfraujoch.

The smaller, unassuming window, the Stollenloch, on the other hand, still plays just as an important role as it ever has. In 1936, after his other partners perished on the face, Tony Kurz froze to death in front of the Stollenloch while rappelling in free space, unable to pass a knot in the rope, just out of reach from rescue workers (recounted in the German film ‘Nordwand’). Clint Eastwood was rescued through this window in The Eiger Sanction. A window which has always served as a trap door for climbers to miraculously transport themselves from the unforgiving alpine face to the civilized world. The window from which many climbers escaped storms including Mugs Stump, who in 1981 after finding this shelter and bounding down the tunnel towards Eigergletscher was only to realize the true horror of trying to plaster his body within the 1-foot clearance of the rocky walls while the immutably time-conscious Swiss train rolled past him (Source: Krakauer’s “Eiger Dreams”). I made sure to have a copy of the train’s timetable in case we had to Gooney our way down this escape-chute/death-trap!

While climbing this route, we were most impressed at the abilities of the early climbers 80 years prior being able to climb on such difficult terrain with such rudimentary equipment: Karl Mehringer, Max Sedlmeyer, Andreas Hinterstoisser, Toni Kurz, Ludwig Vörg, Anderl Heckmair, Louis Lachenal, and Lionel Terray. These climbers were total badasses. Their efforts boggle the mind. Many of the cruxes on this route are no-shit overhangs on brittle rock, downsloping ledges, and poor protection (if any at all).

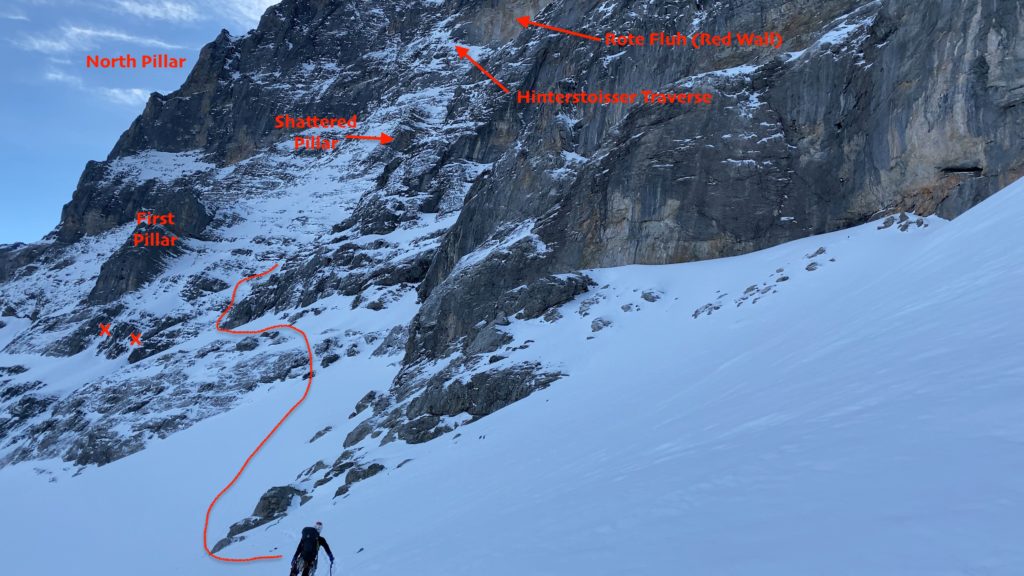

With a pre-dawn start from our comfortable beds at the foot of the Eiger, we stepped out into a frozen darkness. We walked the extra 45min from Kleine Scheidegg up to Eigergletscher on a deserted ski run, passing by several early-morning construction workers who were less-than-enthusiastic about our presence as we tip-toed through the construction site onto the lower snow slopes of the Eigerwand.

A recent blog post by an Italian team had us hopeful that their steps in the snow would pave the way. But alas, we found no steps and instead had to make our path and kick our own steps (later deeming that the blogpost was not clearly dated and was actually from earlier in January). Since much of the route is snow travel, the existence (or not) of another party’s snow steps can drastically alter your timeline in terms of both physical exertion and time spent routefinding.

It is important to intimately know the features on the face, the names of the pitches, the condition of the cruxes. The route was so meticulously memorized as we quizzed each other on the drive up, that it felt as though we were executing a victory lap of versed, choreographed sequences of movements through Nintendo’s Mario Bros (with a princess waiting on top). First, traverse across easy snow slopes towards the First Pillar, zig-zagging across snowed-over limestone ledges up to the Shattered Pillar, and finally the ‘Difficult Crack’, the crux-y start of the actual climbing.

Sadly, we never even saw the Stollenloch. The route passes nearby, but not directly over the Stollenloch, and is very much out-of-the-way. A party behind us on the same day purposefully started late so that they could spend their first night inside the Stollenloch (requiring a good amount digging).

The Difficult Crack is still truly difficult (and also hard to find)! The Difficult Crack is the start of the technical part of the climb. If there is low snow coverage, you’ll have an extra pitch much lower down, before The Difficult Crack (just above the bergschrund and next to ‘the plaque’) which is a straight up rock corner. However, we were able to easily bypass this pitch with an easy snow ramp. Many parties don’t even find The Difficult Crack and instead pick their way up much harder variations to get up to the Hinterstoisser Traverse. It’s especially important to know what the Difficult Crack looks like (keep pictures on your phone) and how to get there (a traverse about 10-15m long heading right and slightly downhill). After that, the rest of the routefinding on the Heckmair is relatively trivial.

The Hinterstoisser Traverse is infamous for its very difficult climbing with snow/ice over blank slabs situated under the impressive overhang of the massive blank face of the Rote Fluh. The Rote Fluh is one of two major obstacles on the face (the other is the Gelbewand), and they are both seriously impressive overhanging faces.

A permanent rope is affixed to the Hinterstoisser Traverse due to its incredible difficulty (everybody pulls on them!) but also as an homage to the 1936 tragedy when the entire team perished while trying to retreat down the face but were unable to reverse the traverse (likely due to fresh verglas plastered to the slabs). Our feeble notion of “free-ing” the Heckmair route quickly evaporated in our minds almost at the very first move of technical climbing. This route is longer and more difficult than we could have imagined, but we were prepared for every obstacle. The mixed climbing is seemingly never-ending and the overhanging steepness of the cruxes were shocking for a route completed 80 years ago.

After the Hinterstoisser Traverse, more fixed lines lead up through a short chimney (‘Swallow’s Nest’) to the First Icefield, which had good névé and offered good step-kicking. A narrow gully connects the First and Second Icefields with the only pure ice climbing pitch on the route: the Ice Hose. If you’re unlucky, the pitch is bone-dry and makes for extremely difficult rock climbing (a variation on its left). Lachenal and Terray opted for the rock variation on the second ascent of the route in 1947, deeming that the WI3 Ice Hose would take too long to chop steps! Nowadays, with modern ice climbing technique, climbers are truly blessed if they find it was we did: in WI3 conditions, heavily featured, and easily accepting “stubby” ice screws.

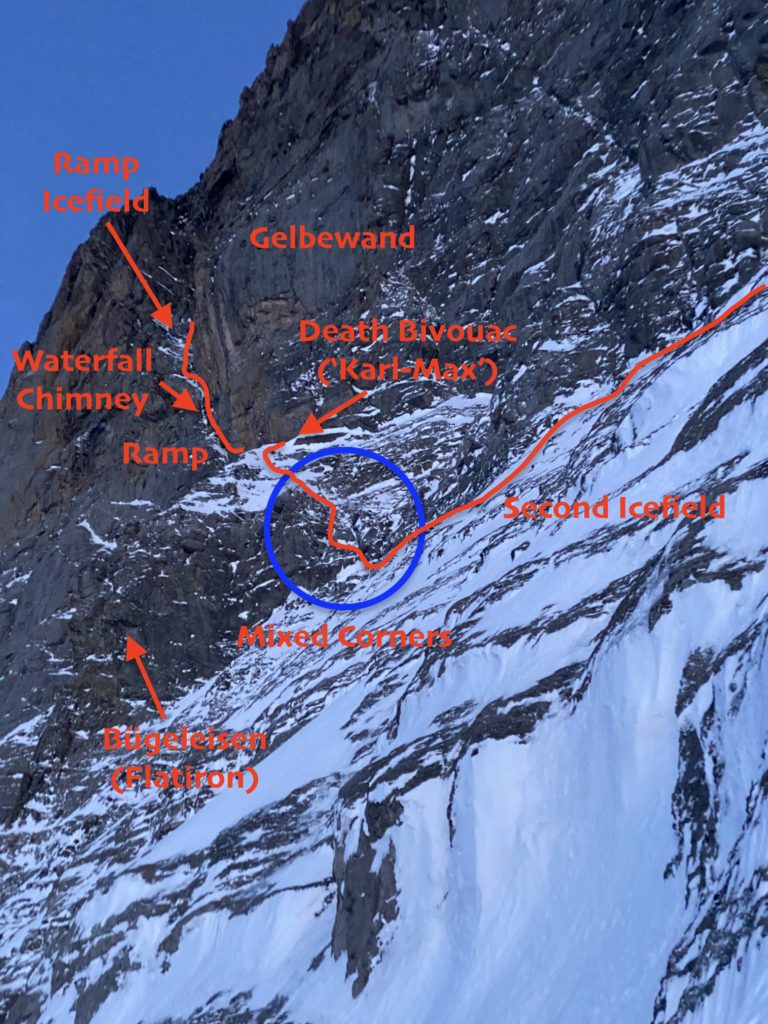

The Second Icefield is a long, snowy traverse on low-angled ground to get to mixed corners (Bügeleisen, or ‘Flatiron’ buttress) and finally to the wall’s first and only decent bivouac: the ‘Death Bivouac’ (aka ‘Karl-Max Bivouac’ where Mehringer and Sedlmeyer froze to death in 1935). It was dark by the time we got to the mixed corners of the ‘Flatiron’ and the climbing was terribly difficult with long runouts and poor protection at about M5. The corners were bare of snow and ice. While leading the pitch, I recalled a story from Barry Blanchard in The Calling of his and Kevin Doyle’s ascent of the Grand Central Couloir on Mount Kitchener where Doyle took off his mitts and licked his fingers so that they would stick to the rock and help his purchase. I took off my beefy climbing gloves in the cold darkness and found the extra stickiness of my bare fingers also provided excellent aid on the downsloping ledges! I could withstand the pain for a few minutes (it was probably 15F outside) if it helped prevent me from falling from my precarious perch.

We finally made it to the Death Bivouac and we had been moving much slower than anticipated all day with only 12hrs of sunlight. Knowing that it was improbable that we would make the summit the next day, we planned to have a short day and bivouac again at the route’s only other decent bivouac: the ‘Traverse of the Gods’.

Here at the Death Bivouac, we had to dig out a platform under a narrow overhang. Surprisingly, our ledge was just wide enough to sleep side-by-side… a welcome and unexpected luxury. We had each brought a thin, lightweight sleeping bag and a short, inflatable ‘summer’ sleeping pad. While brewing up dinner, I was horrified to discover that my sleeping pad had a hole which prevented it from staying inflated. I therefore had to sleep three nights in sub-freezing temperatures on narrow ledges with only ropes and backpacks under my ass!

Every morning was difficult. We woke with the sunlight and made coffee with very little urgency. The entire climb felt rather like a holiday with a very leisurely itinerary and perfect weather. Ashamedly, we spent more time on the face than the first ascent in 1938 and the second ascent in 1947. The face doesn’t receive sun until late in the evening where you are lucky to get 30-60min of direct sunlight on your face.

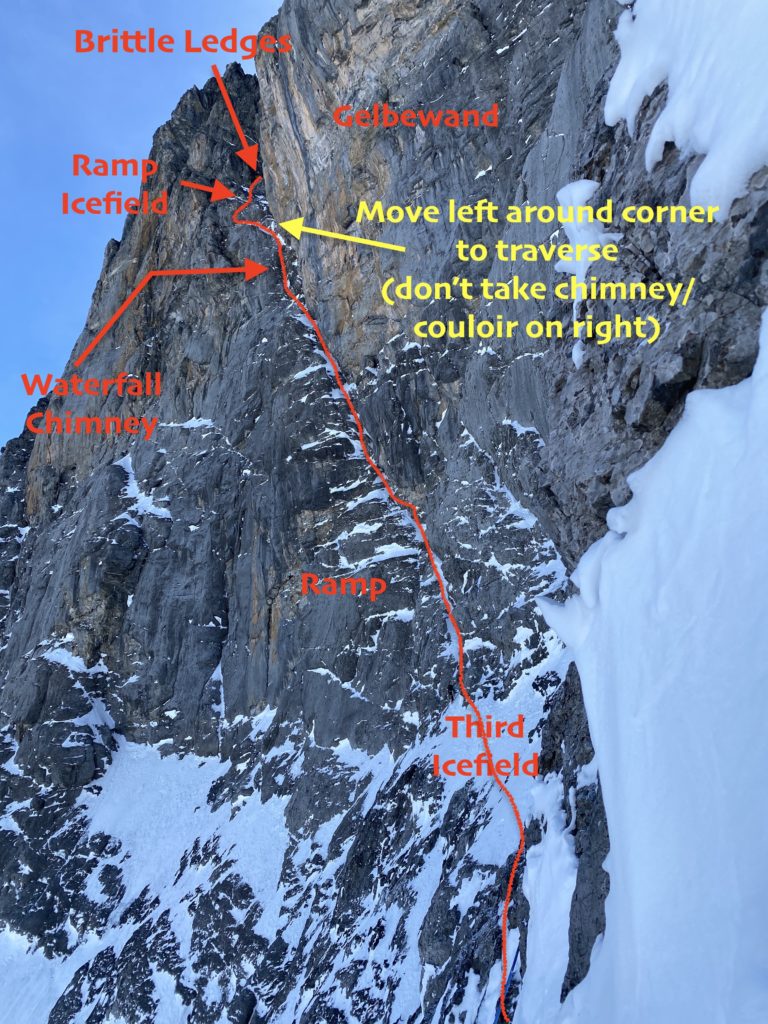

After the Death Bivouac, a short traverse across the Third Icefield leads to ‘The Ramp’, several pitches of easy mixed ground which funnels up to the ‘Waterfall Chimney’ (possibly the crux of the entire route). The Ramp (much like the Hinterstoisser) crawls timidly under another massive overhanging face, the Gelbewand.

The ‘Waterfall Chimney’ is a genuine overhanging chimney of few holds which gushes with water in the summertime. Luckily, being in winter there was no water (good) but also no ice (bad). Usually when climbed in colder parts of the night, the spring/summer thaw freezes and makes the pitch much more palatable. Above here, the route splits into another chimney on the right (not advised) and a tenuous traverse above a head-spinning overhang on the left. The chimney above looked so well protected with fixed ropes and pitons everywhere, but every topo told us to go left around the corner instead. This leftward traverse spits the climber above a dizzying overhang, balancing on delicate, unprotectable limestone discs. A fall would mean a giant pendulum into space, dangling thousands of feet above the concave of the face below. Luckily, a multitude of pitons after a long runout help surmount a final bulge to a short, stout icefield cirque.

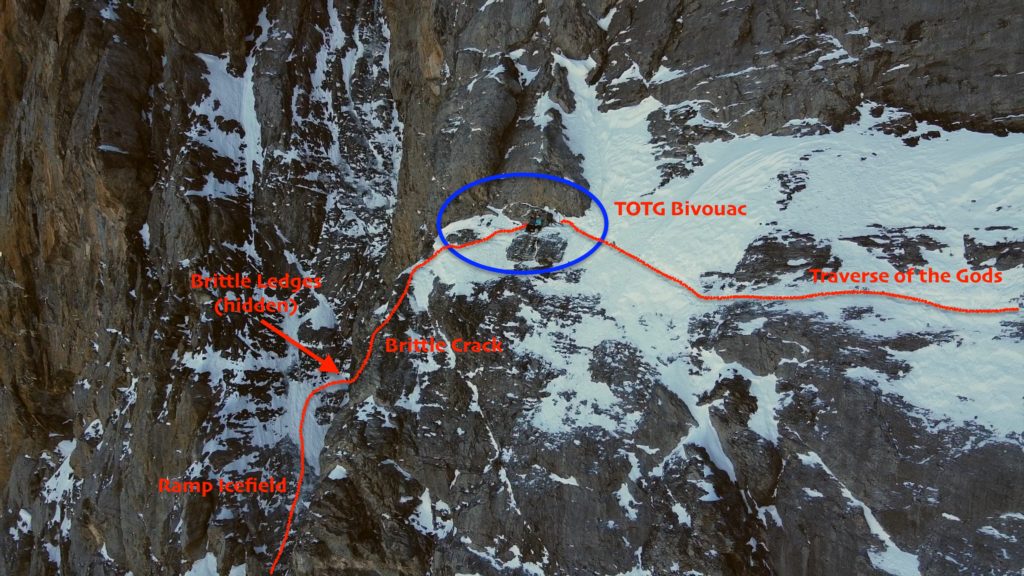

Above this icefield is a steep wall which you traverse on the ‘Brittle Ledges’. In Conquistadors of the Useless, Lionel Terray describes the Brittle Ledges as “tottering, piled up crockery”, which is as best a description as I can surmount. Luckily those piled up crockery are surprisingly solid, making for very interesting traversing on impossibly protruding discs. One final crux to reach our next bivouac: the Brittle Crack. From a hanging belay, you surmount a sizable bulge via perfect hand/fist cracks. This may have been the most fun pitch of the route, gleefully taking off my gloves and jamming my way up solid cracks in sub-freezing temps.

Here, one finds a final bivouac at the beginning of the ‘Traverse of the Gods’, so named because it miraculously provided passage to the final major feature (the White Spider) for the first ascensionists. This accommodation was much narrower than the Death Bivouac and we were forced to sleep narrowly in a line, head-to-toe (with feet dangling off the sides).

A typical timeline is to do the route in 2 days with one bivouac here at the ‘Traverse of the Gods’, making for a VERY big first day from Eigergletscher. The ‘Traverse of the Gods’ takes easy mixed ground rightward to the lower-left appendage of the ‘The White Spider’, a large snow/icefield high on the face. The White Spider is an obvious concave weakness in the wall spotted from the valley floor which was more black-and-blue this time of year than “white”. In winter, the snow/hail sloughs off immediately and the upper part of the face does not get above freezing during the day. Therefore, the White Spider was hard ice for us (instead of easy névé of the late spring and summer). This made for strenuous front-pointing on bullet-hard ice to the final left-trending ramp (the ‘Exit Cracks’) which led to the summit slopes.

Moderate mixed terrain up this ramp ends at a final crux, the 15 meter long ‘Quartz (or Crystal) Crack’ (due to the splotches of Quartz on the limestone face). Sometimes there can be ice in this off-width overhang, but we found it dry. Steve House calls this pitch “Enjoyable when dry”. Priti led this pitch brilliantly, employing virtually every tool in the kit. Another mixed corner leads to a short traverse/rappel on a fixed line to the left-most couloir: the ‘Exit Chimney’.

It was my turn to lead on what looked like an exceptionally fun pitch of easy 5.6 terrain in a wide, hamstring-stretching chimney, of which all three walls resembled a washboard of downward-sloping holds. The crux here is not so much its difficulty as is its headiness. If you’re lucky, there is ice in this chimney (for climbing on and not for placing ice screws in!), but we found it dry as is expected in winter. The limestone is so compact in this chimney that protection does not exist for about 20ft. Your first piton is visible from the bottom of the pitch and you eye it up ravenously as you climb higher. Wide stemming and outward bare-handed palming are more valuable than pure dry tool technique. Here, mono points find value in the corners of the shallow chimney as you try not to look down. A fall would mean cheese-grating on this washboard slab onto a narrow snowy ledge over an overhang into space.

The final moves to the first piece of protection were some of the headiest of my life as I made a dynamic (admittedly ungraceful) throw with my ice tool to the weathered cord hanging from a doubtful piton. After this point, another 100m of much lower-angled couloir climbing takes you to the ‘Summit Snowfields’.

This pain-in-the-ass route never ends!

You still have 200m of easy, mixed terrain followed by another 200m of bullet-hard low-angle ice to finally reach where the summit ridgeline meets the Mittellegi Ridge. We knew the summit was flat enough for a bivy site, but we found a luxuriously wide flat spot earlier, at this juncture with the Mittellegi Ridge. Here, this comfortable bivouac overlooked the Bernese Oberland down to the North and the Ischmeer Glacier (‘Ice Sea’) down to the South, with a brilliant sunset and sunrise.

The next morning was a casual stroll on an easy, snowy ridgeline to the summit as we enjoyed finally being showered in sunlight. Earlier, at the ‘Traverse of the Gods’ a French team of two and a Swiss team of two passed us as we made coffee. We were glad to have people pass us so they would blaze a descent trail down the West Flank of the Eiger. In summer, the descent can be an annoying affair with rappels and down climbing. But in winter, it’s easy snow all the way down to Eigergletscher, and we were glad to have tracks going down the slopes.

We picked up our cached skis at Kleine Scheidegg and enjoyed the victory ski lap down to Grindelwald on yet another perfectly sunny day in a deserted ski resort. As soon as we got back to Grindelwald, we got an automated text from the French government (sent to all French phone numbers) that France was now in lockdown. The next morning, we high-tailed it back to Chamonix to commence 4 weeks of mandatory lockdown.

Timeline

- March 15, 2020: After spending a night at the Grindelwald Mountain Hostel, we skinned from Grindelwald up to Kleine Scheidegg and spent a night at the Hotel Bellevue des Alpes.

- March 16, 2020: Walked from Kleine Scheidegg to Eigergletscher, then climbed the route to the Death Bivouac.

- March 17, 2020: Climbed the route to the Traverse of the Gods bivouac.

- March 18, 2020: Climbed the route to the summit ridge and bivied where it meets with the Mittellegi Ridge.

- March 19, 2020: Walked across the summit ridge to the Summit and descended the West Flanks of the Eiger, walking down to Kleine Scheidegg, then skiing all the way down to Grindelwald.

Selected History of the Eigerwand

- 1935 – Karl Mehringer and Max Sedlmeyer established a line to the First Icefield (much further left on the face from the Heckmair route) and established the path to the ‘Death Bivouac’ where they perished. Their line to the First Icefield is not often climbed and has much more sustained difficulty and objective hazard.

- 1936 – Toni Kurz and Andreas Hinterstoisser established a new line to the First Icefield which then met up with the Mehringer-Sedlmeyer route up to the ‘Death Bivouac’ before retreating in a storm. This new line went up through ‘The Difficult Crack’ and across the ‘Hinterstoisser Traverse’. Hinterstoisser masterfully crossed this difficult slab with a series of strenuous tension traverses. Nowadays, most climbers just pull on the fixed lines across the Hinterstoisser Traverse, although with enough snow and skill, the Traverse can be free’d. Kurz, Hinterstoisser, and two other climbers (Willy Angerer and Edi Rainer) perished on retreat during a storm, as recounted dramatically in the German movie Nordwand.

- 1938 – Anderl Heckmair, Heinrich Harrer, Fritz Kasparek and Ludwig Vorg complete the first ascent via the Kurz/Hinterstoisser variation (reference Harrer’s book The White Spider).

- 1947 – Second Ascent by Lionel Terray and Louis Lachenal (reference Terray’s book Conquistadors of the Useless).

- 1957 – Two Italians (Claudio Corti and Stefano Longhi) and two Germans (Franz Meyer and Gunther Nothdurft) epic on the Heckmair Route in bad weather (scathingly recounted in Conquistadors and White Spider). Only Corti survived. Corti sat for four days on a narrow ledge near the top of the face at the base of the Exit Chimney before a 52-person rescue operation unfolded, finally rescuing him with the use a summit-mounted winch and steel cable. Topo maps still point out this “Corti Bivouac”, however the term “bivouac” is more tongue-in-cheek since this tiny protrusion would no place to spend a night.

- 1961 – First winter ascent, Walter Almberger, Toni Hiebeler, Toni Kinshofer, and Anderl Mannhardt.

- 1963 – First solo ascent, Michel Darbellay, in 18hrs.

- 1964 – Daisy Voog first female ascent.

- 1971 – First helicopter rescue from the face. Today, the company ‘Air-Glaciers’ regularly plucks climbers off the face with reliable mastery.

- 1987 – Christophe Profit free-solo’s an enchainment of the North Faces of the Eiger, Matterhorn, and Grandes Jorasses (the “Alps Trilogy”) in a single push (with paraglider and helicopter transport) in under 42 hours. Many say this event marked the beginning of the era of the “fast and light” style in mountaineering.

- 1991 – Jeff Lowe put up the Metanoia route straight up the middle of the face (solo and in winter) with unparalleled, visionary madness.

- 2007 – Roger Schaeli (“Mister Eiger”, with 52 ascents of the Nordwand at the time of this writing) belayed by Christoph Hainz establish the route “Magic Mushroom” (so named for the iconic mushroom-shaped pillar on the West Ridge on which the route tops out), rated 7c+ (5.13a)

- 2008 – Dean Potter free-BASE’s a Nordwand route called Deep Blue Sea (5.12+) then jumps from the top.

- 2015 – Sasha DiGiulian first female to free “Magic Mushroom”, along with Carlo Traversi

- 2015 – Ueli Steck solos the Heckmair Route in 2 hours 22 minutes 50 seconds

- 2016 – After 25 years, Jeff Lowe’s Metanoia route sees a second ascend by phenoms Thomas Huber, Roger Schaeli, and Stephan Siegrist.

Beta Side-note

Bring a pocket full of Swiss Franc coins! There are large lockers at the Kleine Scheidegg train station to store ski boots (5 Swiss francs), ski lockers (2 Swiss francs per pair of skis), and a high-powered viewing telescope at the Hotel Bellevue des Alpes to look at conditions on the face (1 Swiss franc).

Special Thanks

@eiger_daily (Incredible) for your incredible hospitality, support, and beta; you are truly fostering a wonderful community in the Berner Oberland.

Resources

- Aside from browsing blog posts and Google Images for route overlays, Eigertopo.com is the best route description we found. This little pamphlet provides pitch-by-pitch descriptions as well as informative overlays. This little book is literally all you need!!

- Also check out @eiger_daily (Instagram) for recent pictures of the face and also scroll through the post for the best overlay and gear beta.

- More important beta from Steve House: https://www.uphillathlete.com/climb-eiger-north-face/

- Uphill Athlete Training Plan: https://www.uphillathlete.com/eiger-north-face-training-plan/

- The Italian topo here is VERY descriptive and shockingly accurate. Take belay locations with a grain of salt. Link or simul as many pitches as you can: https://www.camptocamp.org/routes/189333/en/eiger-n-face-heckmair-route

Gear Notes

Single rack #.3-1 (5 cams), nuts, 1 piton (didn’t use), 5 ice screws (2 stubby’s), 2 technical ice tools each, monopoint crampons, light (summer) sleeping bags, puffy pants, big-ass belay parkas, short 3/4 length (summer) inflatable sleeping pad, 60m 8.7mm rope, 6 quickdraws, 4 single-length alpine draws, 4 double-length alpine draws, cordalette, 3 micro traxions for the team (for simul climbing)