K6 Main (the highpoint of the K6 massif) has only been reached once in history, in 1970, by the Austrian Karakoram Expedition of the Vienna Academic Section of the Austrian Alpine Club led by 24-year old Eduard Koblmüller (who would go on to become a celebrated Mountaineer including the first ascent of Southeast Face of Cho Oyu, and a 1983 Rupal Face Ascent).

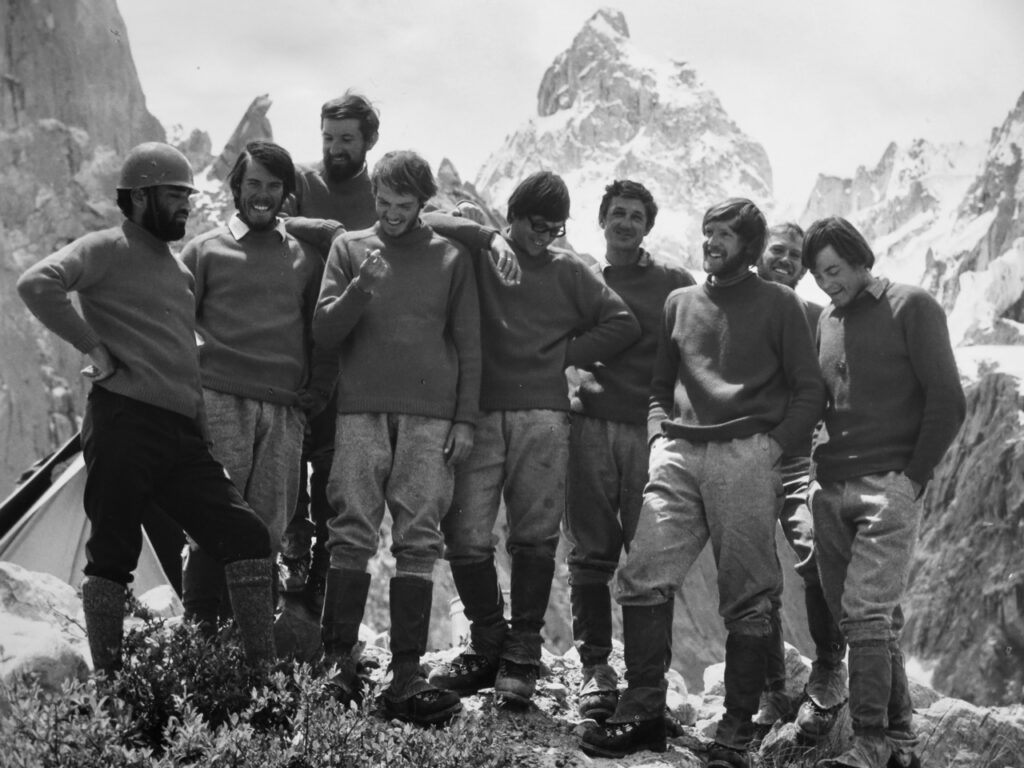

Before our 2020 expedition, we were lucky enough to get in contact with one of the original expedition members of the young Austrian team, Fred Pressl via Facebook, who graciously shared pictures and stories from his 1970 expedition. Pressl would later go on to make the first ascent of Chogolisa in 1975 on another expedition with Koblmüller. I am exceedingly honored that he took the time to share his illuminating experiences, insights, and photographs with us via email (quoted here). On K6, Fred Pressl, then 21, and Koblmüller were accompanied on the expedition by an ambitious and youthful team of Dietmar Entlesberger (28), Gerhard Haberl (24), Christian von der Hecken (25), Helmut Krech (23), Erich Lackner (22), Gerd Pressl (23), and Heinz Thallinger (25), all pictured above.

K6 was not even their main objective. Khinyang Chhish (7852m) in the Hunza Valley was closed, and the permit for their second pick (Malubiting, 7453m) was withdrawn by the Pakistan Government without any reason or information. They were instead issued a permit for K6. You have to be flexible when climbing in Pakistan!

Said Pressl, “In the very last moment, we got some tips about where is the mountain and how to approach, and a thin story about an unsuccessful attempt by the Italians.” (!!!!!!!!!) I can’t imagine just showing up in Pakistan, getting a permit for a random mountain and piecing together thin strips of beta.

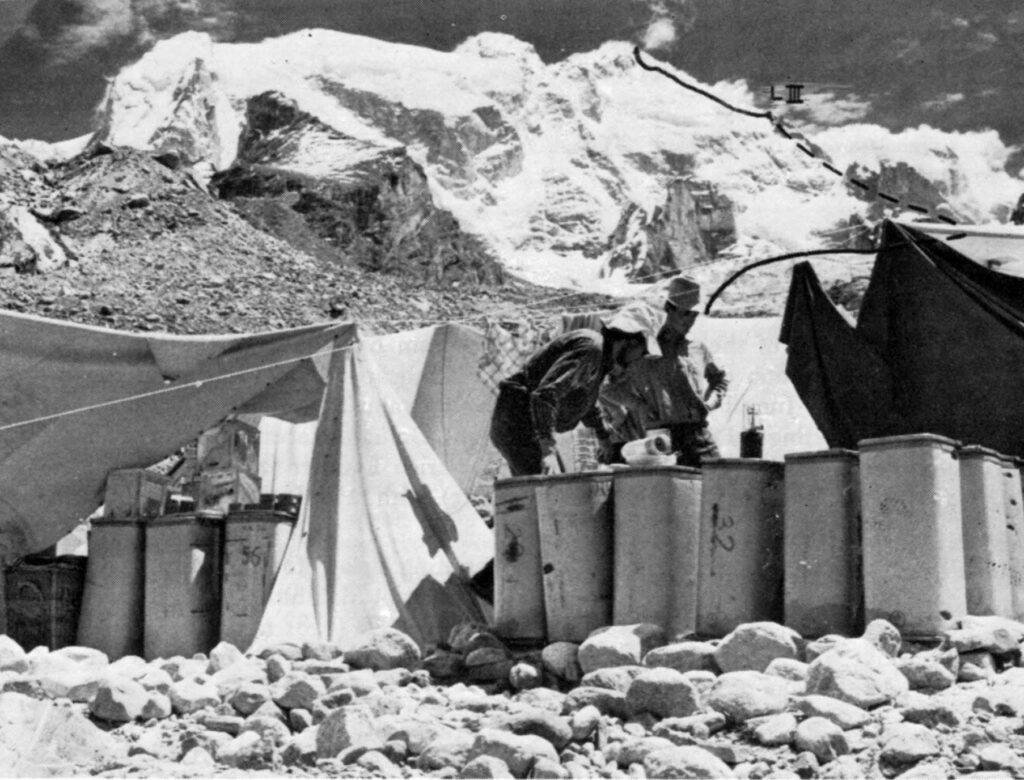

The 1970 team climbed in Expedition style with fixed camps, although they admirably were able to recover all camps at the end of their expedition. They situated Camp 3 at 6600 meters then waited out two weeks of abominable weather at Camp 1. The weather broke, and over three days, Koblmüller, Haberl, Gerd Pressl, and Entlesberger climbed steep snow to the final 200m summit tower. After a 5b A2 rock pitch (above 7,000m!) and an icy gully, they reached the summit on July 17th.

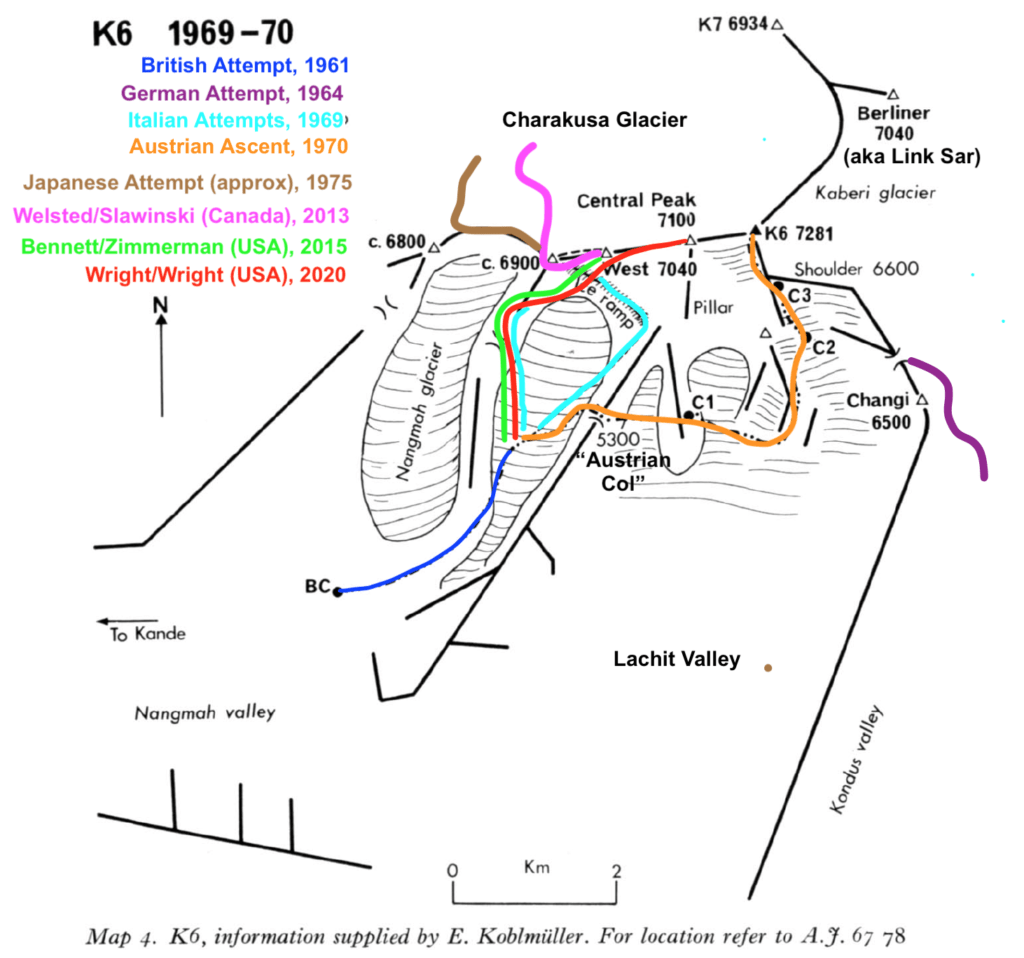

Before the Austrian’s amazing success, the first serious attempt on the mountain was the 1961 British R.A.F. Expedition who spied a potential line up the South Face along a dangerous ice ramp. This line would then need to summit K6 West, traverse over K6 Central, then traverse to the true summit, K6 Main, but they did not make an attempt.

In 1964, a Berlin Karakoram Expedition did some reconnaissance from the completely opposite side of the mountain, the Kondus Valley, but found only difficult access to the mountain from that side.

Another team from the Italian Club of Abruzzi led by Luigi Barbuscia in 1969 attempted the mountain following the 1961 British ice ramp with the intention of traversing from K6 West to K6 Main along the technical ridgeline all above 7,000m. We found some old climbing gear left in situ on the West Face (well far away from the “ice ramp”) which may have been remains from an alternative reconnaissance from the 1969 Italian team.

The 1970 American Alpine Journal summarized the 1969 Italian Expedition: “An Italian expedition, led by Luigi Barbuscia and composed of Guido Machetto, Carlo Leone, Nicola Marcantante, Domencico Alessandri and Dr. Bruno Marsilli attempted to climb K6 (23,890 feet) by a route which they felt might be possible. It rises up the 6500-foot west wall to 23,100 foot foresummit. Bad weather drove Alessandri and Leone back when they were close to the foresummit and only 800 feet from the top. The expedition did geological work in the Hushe valley.“

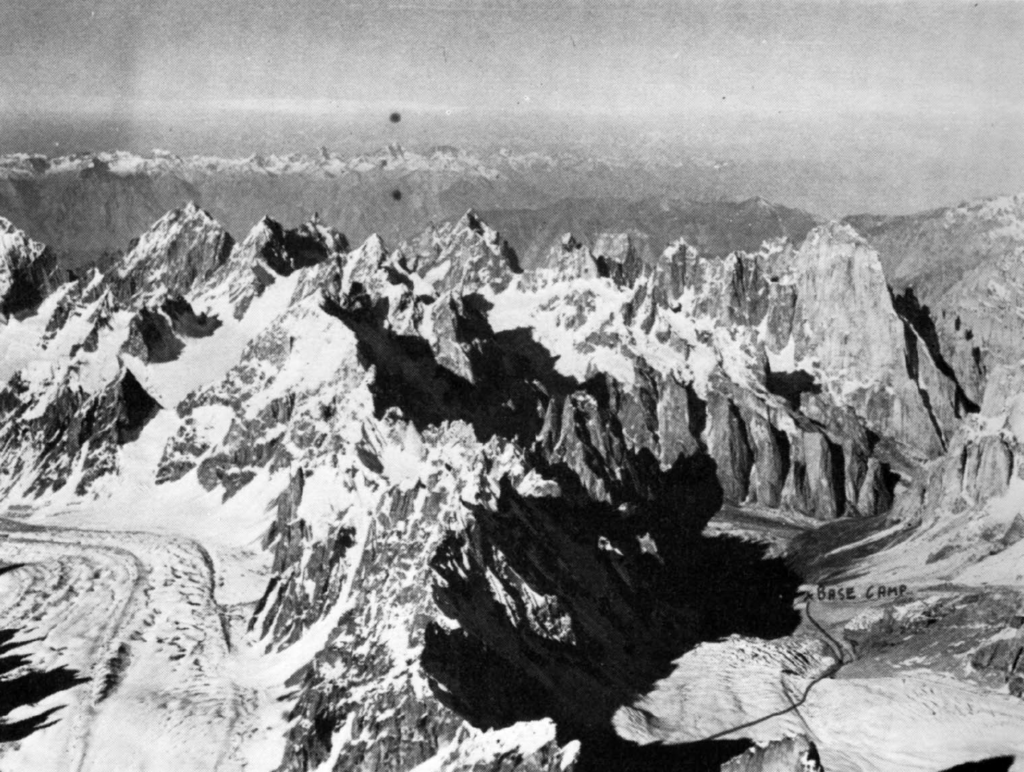

The 1970 Austrian team tried yet another completely unknown glacier basin at the end of the Lachit Valley, accessing it by going up the Nangmah Valley and crossing over a high col along the South Face to reach the Lachit. They were finally successful in reaching the summit of K6 Main via the Southeast Ridge. This glacier basin would later serve as the same approach for the 2015 FA of nearby Changi Tower (6500m) by Swenson/Zimmerman/Bennett.

Fred Pressl shed some more light on their incredible 1970 expedition as they travelled by Volkswagon Bus and truck from Vienna through Central Asia all the way to Rawalpindi and back. They faced many logistical hardships which used to be the norm for Karakoram climbing. First, the overland route from Gilgit to Skardu was prohibited by the Kashmir Government, and Pakistan International Airlines had no more transport planes, so they had to charter their own private plane. Once in Skardu, they took the adventurous jeep road to Kapalu (it’s still pretty adventurous today!).

From Kapalu, in order to cross the Shyok River to access the Hushe Valley, the 1970 expedition relied on basic rafts to get all of the gear across. Pressl continues, “On our way back, the porters went on strike and the raftsmen too. We constructed a ‘boat’ with 10 air mattresses and ski poles and transferred everything back over the river to Khapalu thus becoming a long-living legend in the area.”

Only as of A FEW YEARS ago, there is now a very nice, sturdy, modern bridge (the “Saling Bridge”) for vehicles to cross the Shyok. From Kapulu, 100 porters accompanied the 1970 team for 100km up the Hushe Valley to the Village of Kanday, and finally into the Nangmah Valley. Nowadays, there is a decent road from Kapulu to Kanday, and most of our porters come from this village instead of the more distant Kapulu.

The Nangmah Valley is an Easterly offshoot to the Hushe Valley which itself is an impressively straight-as-a-baton valley, oriented almost directly North-South and easily identified on a satellite image of the otherwise overwhelmingly complex topography of the Karakoram.

The South Face of K6 is so deep up the valleys that, although a massively impressive face, hasn’t even been viewed by many of the local villagers (including our own Base Camp cooks, who had very little interest in the 1hr trek further up valley to view this face).

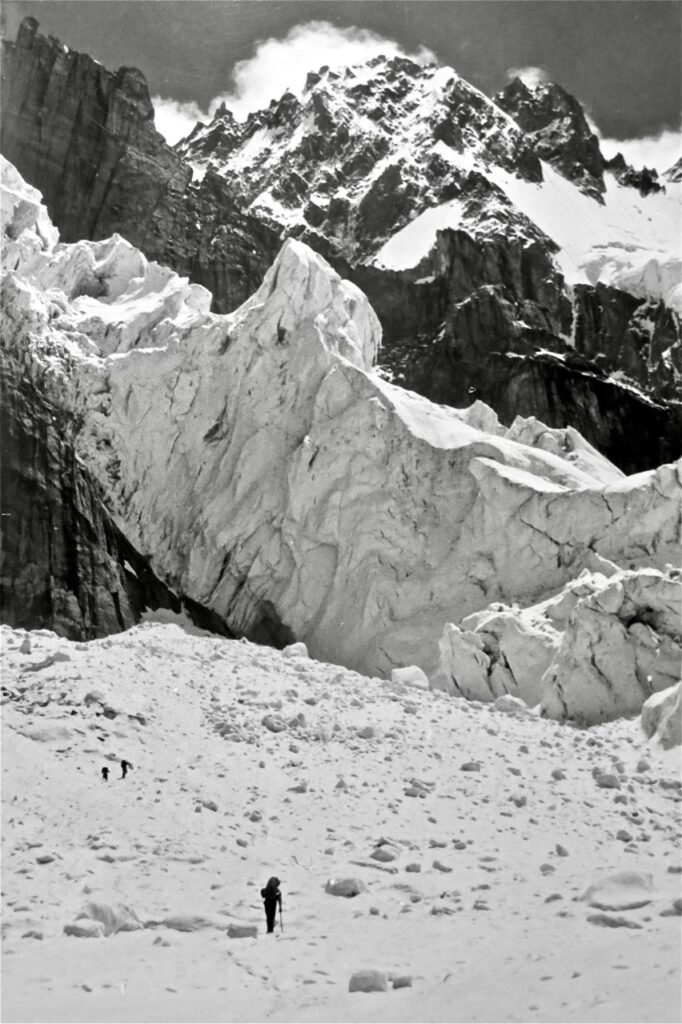

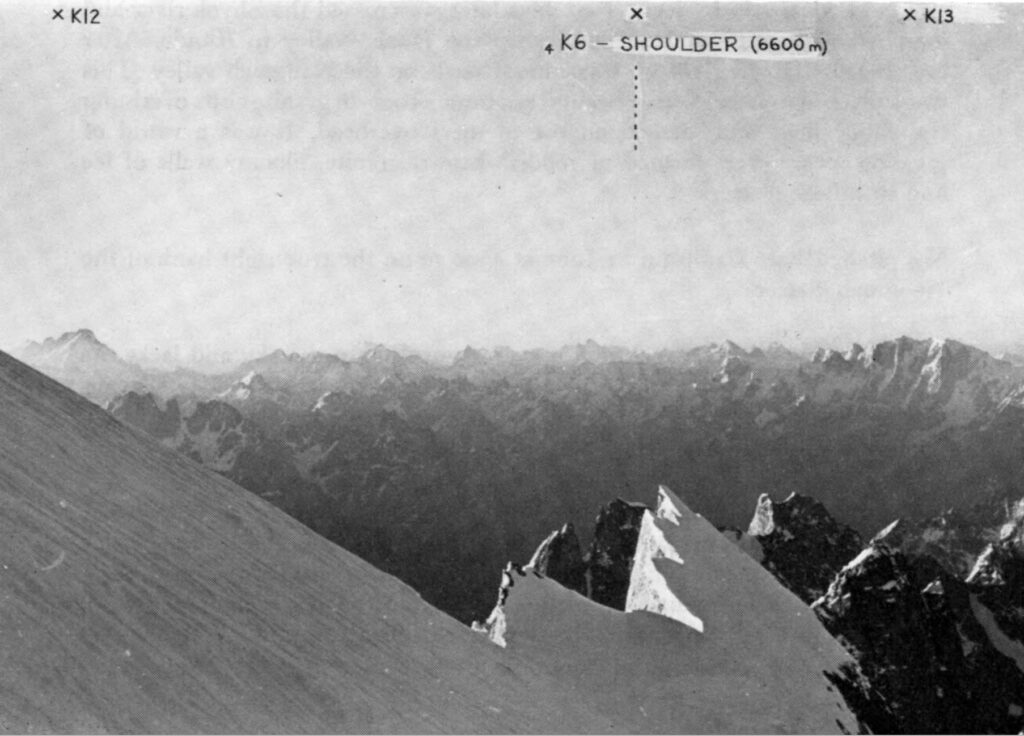

Pressl writes, “We were lucky to find a hidden route up the mountain on the far east side. We had to cross a ridge to the east to the neighboring glacier basin where we put up our first camp. From there on, we found a hidden couloir with a scary entrance under towering seracs. The way up is extremely beautiful and without bigger problems. Our third and last camp was at 6600m. The crux at least was the 200m summit rock which was prepared on one day to summit on the other day. (5a and b)”

The Pakistan Times headlined their ascent “Youngsters Succeed Where Veterans Failed.” They were all students at the time, already with experience in the inner Hindu Kush in 1968. Faced with further logistical challenges, the President of Austria intervened on their behalf to lobby the Pakistani government to allow the team to drive overland out of Pakistan via an old and forbidden road through the Indus Valley since there were no flights out of Skardu for weeks.

Pressl’s email continues on a personal note: “I am sure that you will have every support by the locals today. For you as vegetarians look out for fresh onions and garlic as well as rhubarb where there are in abundance. Porters will bring you fresh eggs and apricots and fresh cheese.” Indeed, we appreciatively encountered much support and affection from the locals (but sadly, no rhubarb!).

K6 is the 88th (or 89th, depending on the list) highest mountain on Earth, and the 40th highest in Pakistan. K6 Central was perhaps the 20th highest (or so) unclimbed peak on Earth and has a meager prominence of approximately 150m. It is located in the Masherbrum Range within the Karakoram Mountains of Northern Pakistan, in Gilgit-Baltistan.

K6 is a hulking massif that towers over the surrounding Masherbrum Mountains in the Gilgit-Baltistan Region of the Karakoram Range. While it lacks the elegance of the striking Masherbrum and Chogolisa peaks nearby, it makes up for in shear volume and breadth. It is the tallest peak in ~15mi in all directions. The great 8000ers of the Baltoro Glacier are also only 20miles to the North. K6 is flanked by several major glaciers: Charakusa to the North, Nangmah to the South, Lachit to the Southeast, and Kondus to the East.

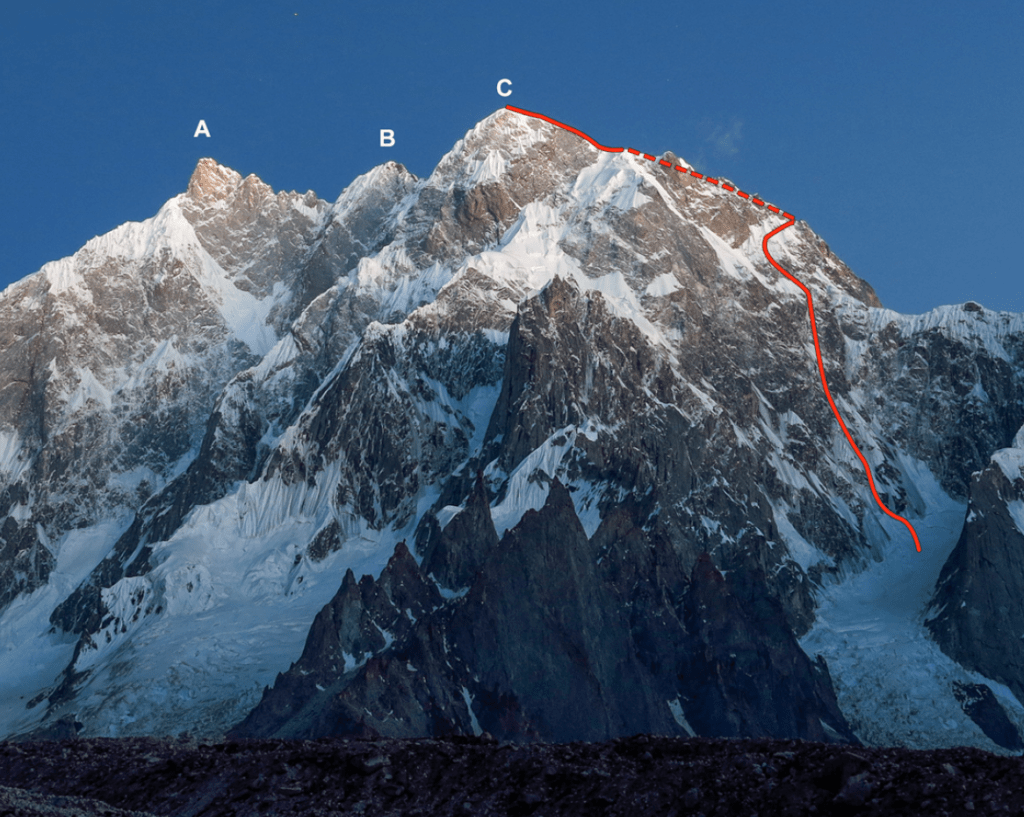

K6 has three major summits along its summit ridge: West (7,040m), Central (7,100m), and Main (7,281m). While the height of only K6 Main has been accurately surveyed, the other two were not. Eberhard Jurgalski (of 8000ers.com) estimates the heights of Central to be about 7,155m and West about 7,140m from SRTM data which matches our observations.

The 1969 Italian team did not publish any reports of their trip. Therefore, other than the fact that they did not reach K6 Main, it remained unclear how far up the South Face they reached. Did they summit K6 West as Koblmüller’s 1970 map suggests? It wasn’t until 2004 that a document published by the Italian Alpine Club at the time of Luigi Barbuscia’s death stated that the 1969 team managed to get two members up to 6,850m. This publicized admission meant that both K6 West and K6 Central remained unclimbed.

The North Face of K6 is exceedingly daunting and much more photographed as it is situated at the end of the much more accessible Charakusa Valley. A Japanese Team (Toyama Sanyu-kai Expedition, led by Shoko Saegi) attempted the mountain for the first time from the North (Charakusa Valley) in 1975. Ian Welsted writes: “1975 saw a Japanese expedition try a novel approach to the problem, traversing an entire 6,000 meter peak , Kapura, in an effort to reach the easier southerly slopes from the Charakusa Valley. The effort ended at 6,900 meters.”

Tensions between India and Pakistan at the Actual Ground Position Line near K6 left this mountain relatively quiet for four decades.

Steve House first spotted a new line up to K6 West on North side of the mountain up the Charakusa Valley in 2003 which starts from the “First Charakusa Cwm”. He returned in 2004 to complete his historic solo of K7, but did not make a serious attempt at K6 West. Again he returned to the Charakusa in 2007 with Vince Anderson and Marko Prezelj but found unstable snow conditions. They shared the same objective of K6 West that year with Canadians L.P. Menard and Maxime Turgeon who became injured during their trip. Due to snow conditions, House, Anderson, and Prezelj moved on to a different objective completing the first ascent of K7 West that season.

In 2013, K6 West again had two competing parties far below on the Charakusa Glacier who were set on Steve House’s 2003 vision. The Japanese Kenshi Imai, Kimihiro Miyagi, and Kenro Nakajima (having heard of the route from Marko Prezelj) made impressive progress for over a week up the route to approximately 6300m, but returned during a heavy storm. Canadians Ian Welsted and Raphael Slawinski (both venerable Alpinists) then launched their own assault at this highly technical line (1,800m, WI4+ M6+), reaching the virgin summit of K6 West, a climb for which they were awarded the Piolet d’Or.

Humorously, Pressl contends “The Canadian boys who did this incredible climb from Charakusa Valley could not know that they were not the first ones up there.”

In 2015, Graham Zimmerman and Scott Bennett became the second ascensionists of K6 West approaching from the South (Nangmah) side following a new route along the Southwest Ridge after bailing from their original plan to attempt K6 Central via the South Face’s Central Buttress which proved to be too dangerous. The pair impressively also made a first ascent of nearby Changi Tower along with Steve Swenson on the same expedition. Swenson and Zimmerman would go on to complete the first ascent of nearby Link Sar with Chris Wright and Mark Richey in 2019 to earn them a Piolet d’Or (Swenson’s second).

On K6 West, Zimmerman and Bennett perched their final camp atop the SW Ridge at 6,500m to do a day trip up to K6 West, completing the second ascent. Incoming weather drove them back to Base Camp before they could attempt K6 Central. K6 Central remained unclimbed.

Ariella Gintzler concluded her Rock & Ice article on Zimmerman and Bennett’s climb as follows: “Both Zimmerman and Bennett hope to return to the Karakoram, though, another shot at K6 Central is not on their radar.” Our 2020 expedition would be our first to the Greater Ranges, and finding an engaging objective in such a topographical maze was absolutely daunting; it seemed supremely obvious to us to lovingly borrow someone else’s vision!

We checked in with Graham Zimmerman after hearing him give a presentation on his Karakoram success in Seattle to ask for his blessing, to which he responded “Send that shit!”

Eduard Koblmüller, the leader of the Austrian Expedition, describes the Italian’s 1969 attempted line from K6 West to K6 Main as follows : “If this route [from K6 West to K6 Main] were attempted it would be necessary to follow the very long West ridge of the mountain to the summit tower, the second portion [after K6 Central] of which is dominated by the huge gendarmes.” Our primary objective was not only to summit the virgin K6 Central but also continue along the interesting ridgeline to make a second ascent of K6 Main. This stretch goal was not to be, since we were already very late in the season, encountering jet stream winds and bitter cold above 7,000m in October. The impressive gendarmes between K6 Central and K6 Main are still untouched.

Some further advice from Fred Pressl which we received before our trip: “I guess that you can attack the [South Face] icewall right up from the [Lachit] glacier basin to get up without touching the scary couloir [the 1970 Austrian route]. If you have time, you can even try to cross the mountain to the west while climbing up and down the pinnacles will be a hard job.” Sage advice, and yes it would have been a very hard job, indeed.

In addition to Graham Zimmerman and Fred Pressl, we’d like to also extend our appreciation to Steve Swenson who met us in Seattle to offer advice on our first expedition to the Greater Ranges. In fact, it was his book ‘Karakoram: Climbing Through the Kashmir Conflict” that inspired us to go in the first place. Furthermore, Ian Welsted graciously sent us previously-unpublished beta photos and advice on the traverse from atop K6 West. He humorously described the mile-long traverse above 7,000m objective as being “very French”.

Further Reading:

http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/13201212961/Learning-to-Walk

http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/12200834600

http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/13201214001

http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/12197653002

1 Comment

Toni Edelmayr · April 21, 2021 at 4:45 am

It is so cool to read this story as a member from the same alpine club of one of the expeditioncrew (Gerhard Haberl) Thank you very much for this amazing article.

All the best from austria, Toni

Comments are closed.